The Technological Economy

1/15/2014

I love being a software developer. Once I've performed a task a few times, I can then write some code to perform that task for me. This is fantastic! It allows me to continually focus my mind on new and exciting thoughts. The result is that I'm never bored.

All around the world, people like me are creating software and other technology that takes routine labor out of the hands of human workers. But what are the social and economic implications? The purpose of this blog is to explore that very question. For years I've been mulling over the topic of automation and, during that time, I've re-evaluated many of my personal political and economic preconceptions. Until now, any record of my thought process existed only as a fragmented series of Facebook debates and email threads.

I'll start with what I know. I know that if automation continues over the long term, we'll steadily move toward a future in which humans will no longer be required to perform routine labor. That sounds like a good thing, but is it? What will happen to jobs? Will people even have jobs in this future? Surely, there will always be worthwhile ways for people to spend their time, but how does that relate to the labor market?

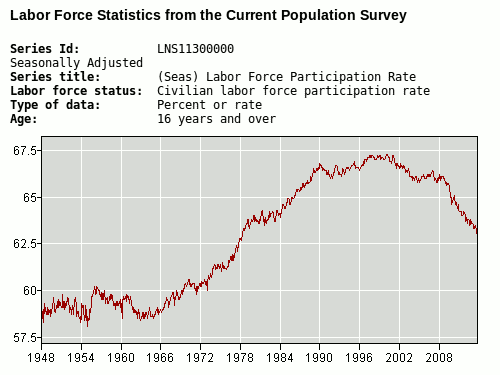

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, today (Nov 2013) in the USA, 63% of citizens over age 16 participate in the labor force. We peaked at 67.3% in the year 2000 and have been steadily declining since. Our current labor force participation rate is the lowest it's been since 1978:

This statistic includes everyone who has a job and everyone who's looking for a job. As you can see, the labor force participation remained fairly consistent at around 59% until the mid 1960's and then steadily increased for a couple decades. That increase corresponds to the feminist movement during which more women began to enter the labor force. That makes sense. But why is labor force participation coming back down again? Is it good? Is it bad? How much of this change has been influenced by automation? Are we moving back toward an economy of single-earner families or are we moving toward an economy in which some families earn while others don't? Can the trend be reversed? Should it be reversed?

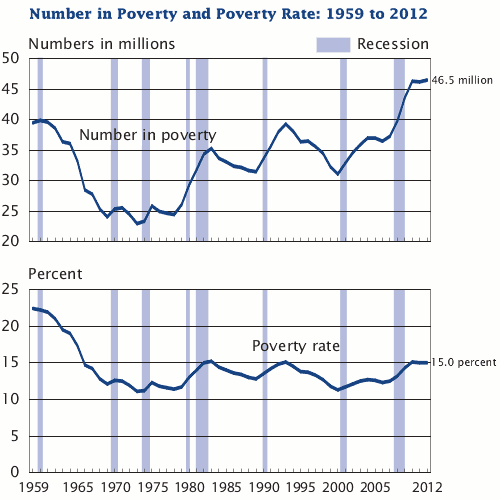

According to The United States Census Bureau, 15% of our citizens live in poverty:

The Census Bureau measures poverty by defining as poor anyone whose income falls below a certain threshold. That makes sense. Money allows you to buy the things that make you not poor (food, a house, health care, education, etc.) People debate endlessly about where we should set the poverty threshold, but the line is somewhat arbitrary. Should our goal be to eliminate poverty up to an arbitrary threshold and then stop? Or should we be aiming to continually maximize our individual and collective wealth? In what ways do jobs mitigate poverty? As automation progresses, is it reasonable for us to continue to expect jobs to provide for people's basic needs and beyond?

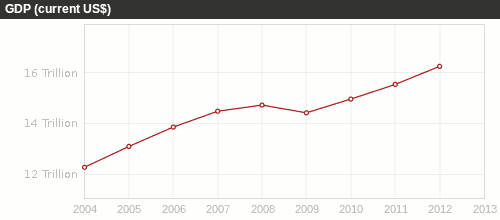

The World Bank says that The United States GDP is increasing, even when adjusted for inflation:

The Gross Domestic Product is a measure of how much stuff we produce. But how much of "we" is people? What is automation's role in the GDP? Has the GDP increased without additional contribution from labor? How does our GDP relate to the GDPs of other countries? If we're continually producing more stuff, why is poverty not declining? How does global poverty relate to the poverty of individual countries? In the fight against poverty, have we taken full advantage of our increasing abundance?

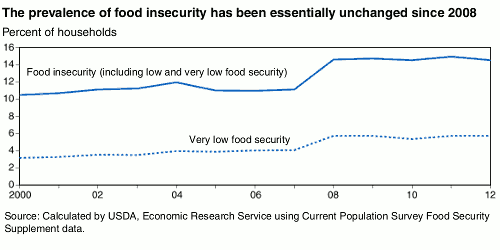

According to a recent USDA Report, 14.5% of United States Households in 2012 were food insecure. That's up from 10.5% in the year 2000:

Food security means access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.

We have no need to draw an arbitrary hunger threshold. People either get enough food to eat or they don't. That makes hunger seem like a simpler problem to solve than general poverty. But while the GDP rises, the nutritional requirements for a human body remain constant. So why are more people in this country hungry than were hungry twelve years ago?

I began seriously exploring many of these questions as a result of the ongoing public debate about intellectual property (copyrights and patents). Computers and the Internet have automated away the labor involved in information distribution. We haven't seen such a leap in distribution efficiency since the invention of the printing press in 1450. Creators can now share their work with the click of a mouse button. That's amazing, but what does free copying mean for industries that have built themselves around the ownership and distribution of intellectual property? What does it mean for jobs in those industries? Do our current intellectual property laws make sense for a world in which copying is free? How do they help? How do they hurt?

I've asked a lot of questions in this post and I'm excited to explore them further. Technology is changing the face of our society in ways we don't fully understand. It's taking us places we never imagined. I'm not sure where we're going and I'm not sure how we'll get there. But I know I'll feel better if we can take this journey together.